Irena Russocka (Rothenberg) Archives

The Countess from Stryj

The Life of Irena Maria Russocka (née Róża Rothenberg / Sołomirecka) compiled from archival records and family memories.

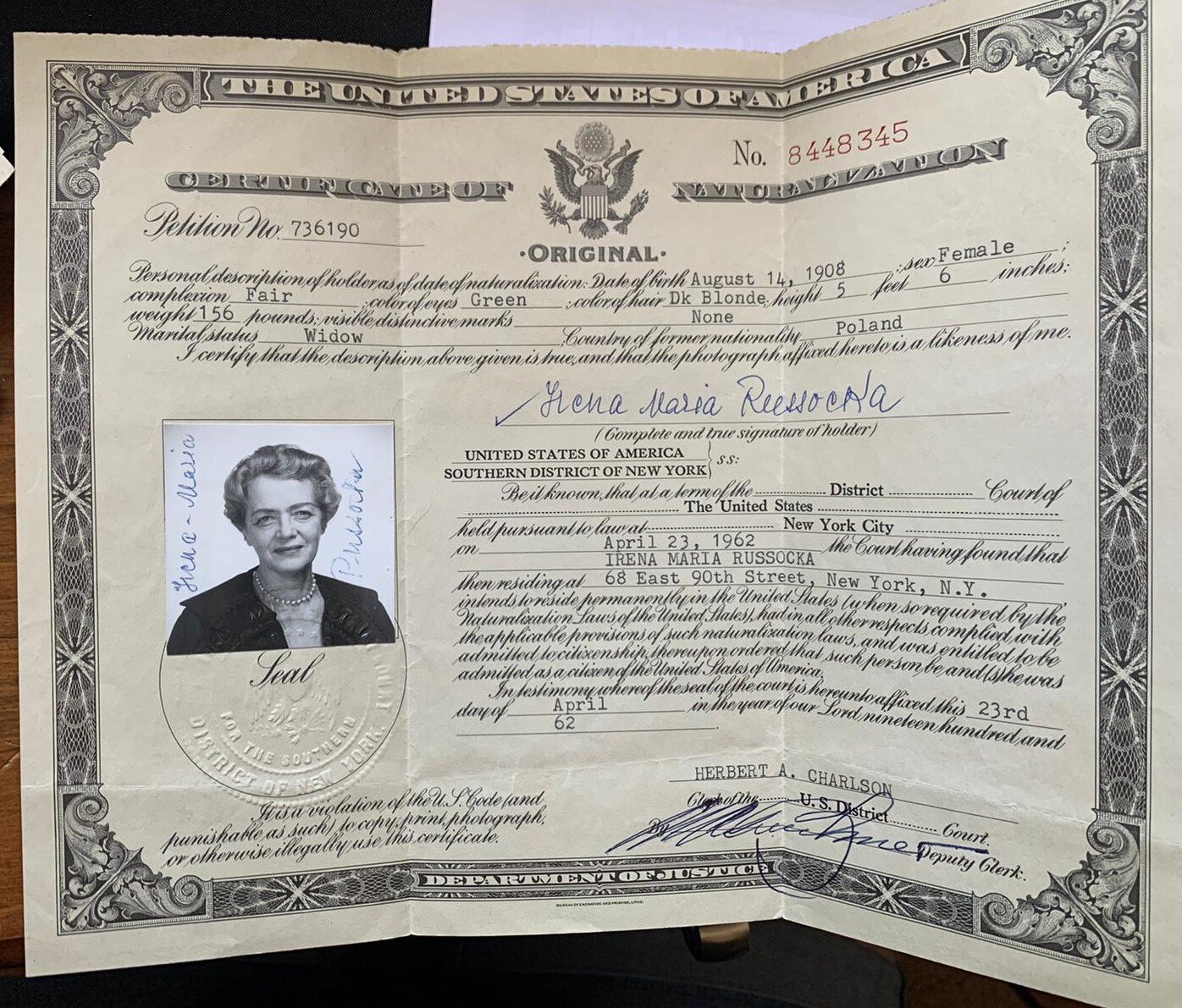

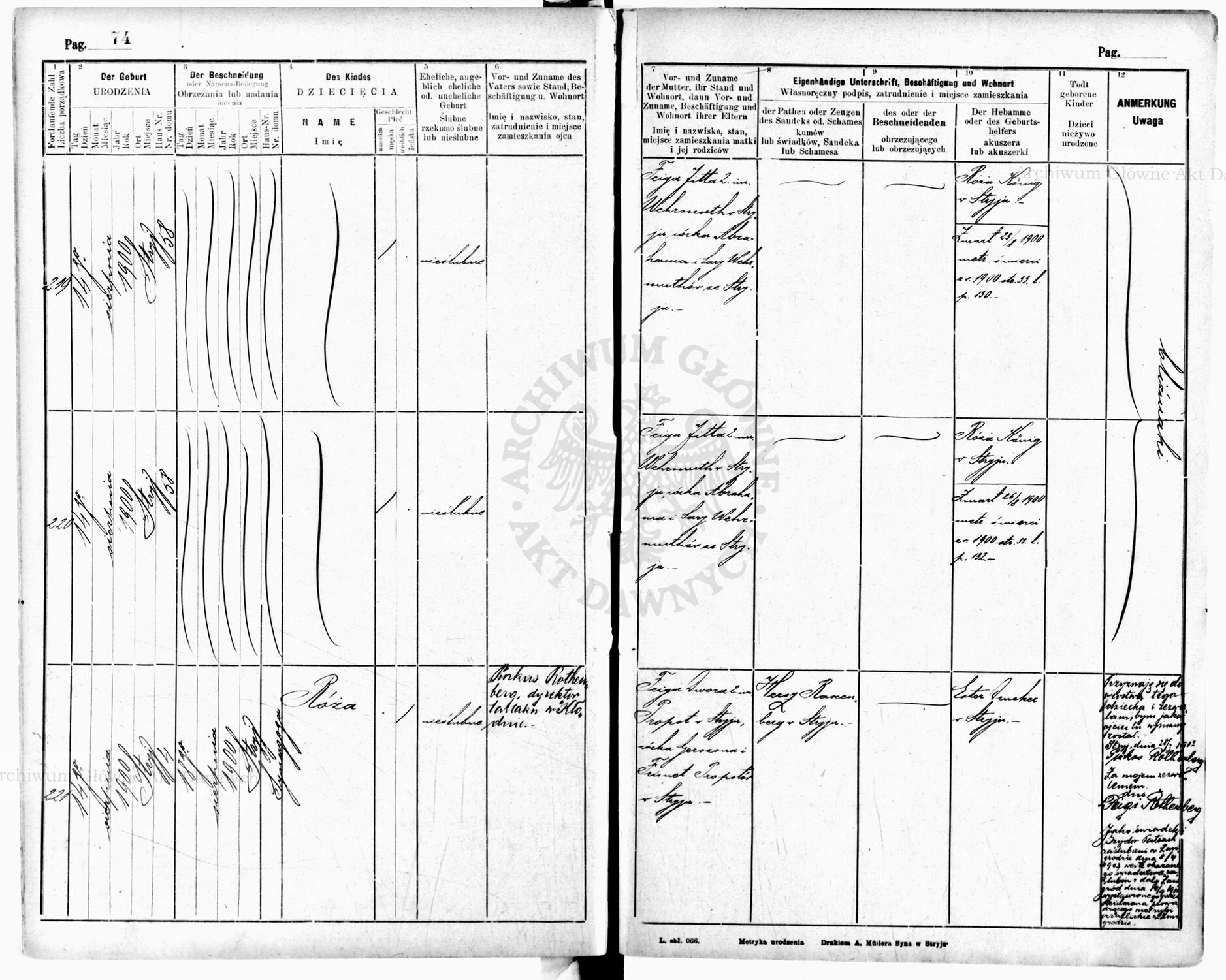

Irena Maria Russocka’s life was shaped by reinvention, survival, and silence. Born into a Jewish family in the Galician town of Stryj on 14 August 1900 (sometimes recorded as 1903), her original name was Róża Rothenberg, the illegitimate daughter of Feiga Dwora Probst and Pinkas Rothenberg, a manager of a sawmill in Kłodno. Her early birth record lists her as born in house no. 4 in Stryj and later registered at house no. 96/97. Though born out of wedlock, Pinkas acknowledged paternity in 1902, and her parents married shortly afterward, in 1903 in Żmigród. Her mother came from a local Jewish family; her maternal grandfather Gerschon Probst was a cattle trader in Stryj, and her maternal grandmother Frimet died young.

Galicia in the early 20th century was a diverse, contested region of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, home to Poles, Jews, Ukrainians, and Germans. Róża’s upbringing in Stryj would have placed her within the vibrant, though increasingly precarious, Jewish bourgeoisie. Her father's position in the timber industry placed the family among the growing class of Jewish entrepreneurs in the region, often caught between the promise of integration and the threat of rising antisemitism.

Birth Record

Róża (left), her mother, Francziska Propst and sister Malie circa 1907

Images of Stryj at the turn of the century.

From Róża to Irena

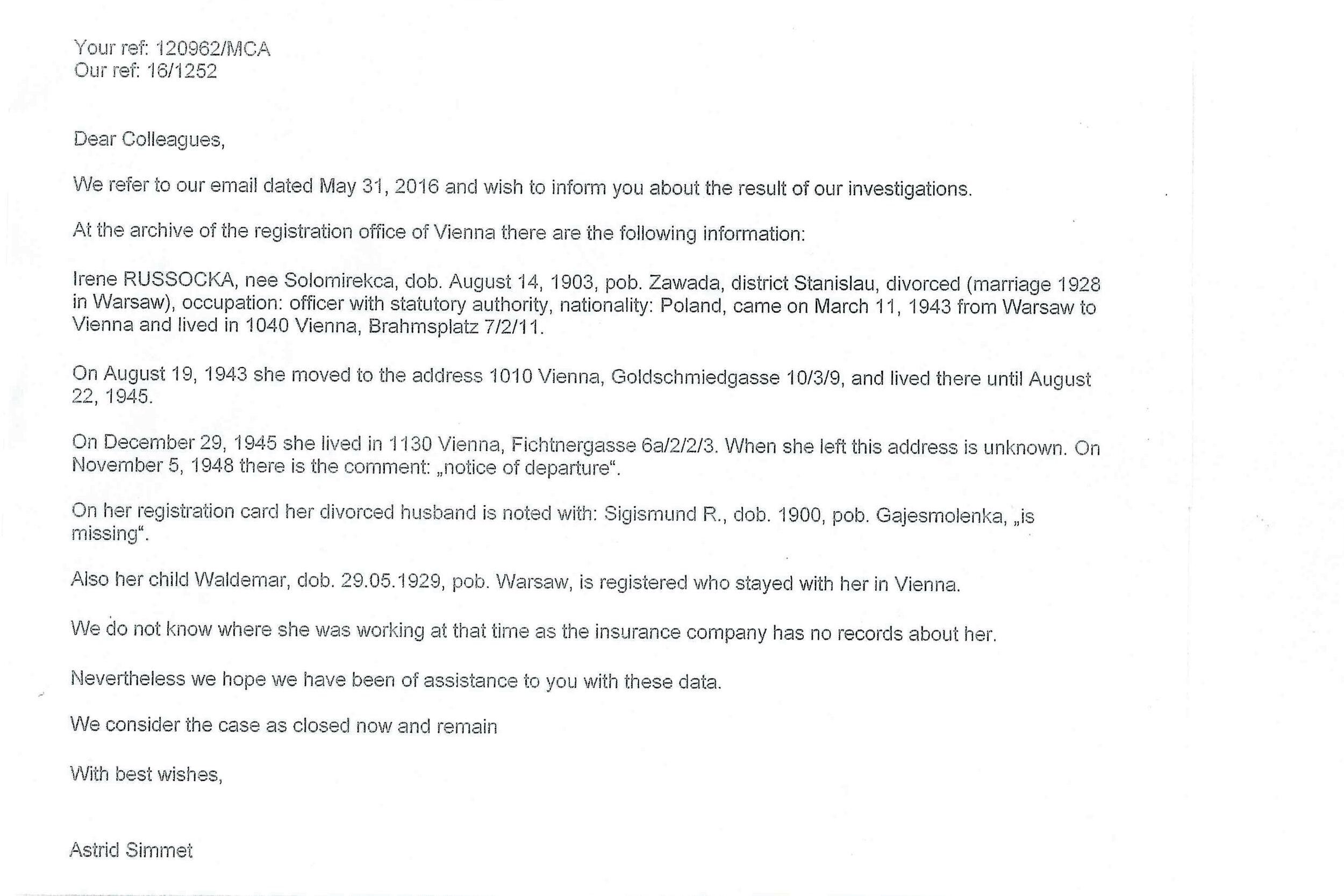

At some point between the end of World War I and her marriage in 1928, Róża changed her name and religious identity, becoming Irena Maria Sołomirecka, a name suggesting a noble or gentrified lineage - possibly a Polish Catholic reinvention intended to ease social integration or facilitate marriage. Records indicate that the name change may have been formalized and published in official bulletins like Monitor Polski, though such documents have yet to be traced.

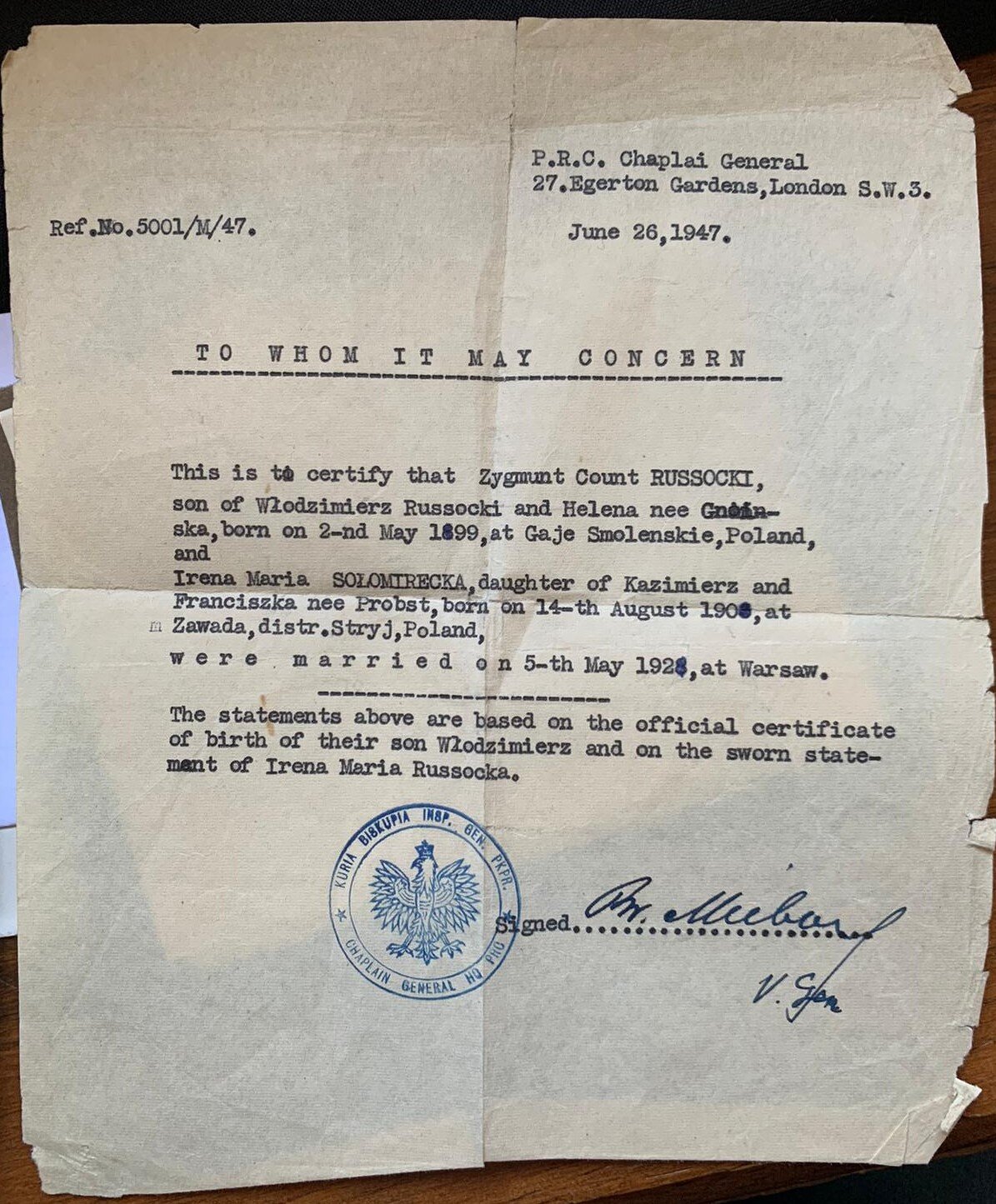

Irena’s marriage to Count Zygmunt Władysław Emil Józef Maria von Brzezia Russocki on 5 May 1928, in Warsaw’s Church of the Holiest Saviour, cemented her position in Polish aristocratic society. The church record, however, still ambiguously records her parentage: she is named as the daughter of "Paweł" (a possible Polonization of Pinkas) and Franciszka née Probst, suggesting an intentional rewriting of her Jewish identity.

Zygmunt (a member of a notable Polish noble family with estates near Kołomyja) was a Catholic landowner born in Brody (also in Galicia), and the union between a converted Jewish woman and a Polish count was rare, though not unheard of in interwar Poland. It appears the marriage was socially accepted, at least superficially. The couple had one son, Włodzimierz Maria Russocki, later known as James Russocki, born in Warsaw on 29 May 1929.

The Russocki family’s genealogy has been studied by experts such as Tomasz Lenczewski, who noted that Irena’s Russocki relatives were reticent to publicly discuss her lineage, a reflection of the era’s social pressures and the stigma attached to Jewish ancestry. Notably, Irena herself did not disclose this origin to her son James (Włodzimierz) Russocki, who never knew of it. Contacts within the broader Russocki networks, including noble lines in London, corroborated the sensitivity surrounding these family histories.

Marriage to Count Zygmunt Wladysław Emil Józef Maria Russocki 1928

Translation:

It happened in the Administrative office of the parish of Zbawiciel ( Redeemer), 5th May 1928 at 11A.M . Let it be known that in the presence of witnesses Witold Grzybowski , landowner and Władysław Gnoiński , official of the Catholic parish , first witness residing on Rurzki Estate , in the district authority office of ?ochewski and the second in Warszawa . A religious marital union took place between Zygmunt Wladysław Emil Józef Maryja, Count from Brzeci Russocki , age 30 , bachelor, landowner, born in Gaju ( Grove) Smolinski, district of Broda, son of Włodzimierz Józef Wiktor and Helena née Wincentyna née Gnoiński, residing in Warszawa on ulica Róziej ( Rose Street ) #3 and Miss Irena Marja Rotenberg Sołomirecka , age 24. Bride lives with father. Born in Stryja, daughter of Paweł and Franciszka, née Probert, residing in Warszawa on Koszykowa Street, #11 . The marriage was preceded by the announcement of three banns , one in the parish church of Św. Antoniego (Saint Antnony) and Św. Krzywa ( Holy Cross) on 8th April this current year. The other two were in the Cathedral in Lwów by the Archbishop of Warszawa on 11th April, this current year , number 1980 . The newlyweds confirmed that they had no prenuptial agreement. This religious rite was performed by Father / Pastor Edward Swięckiego , curate here . This record was read by newlyweds and witnesses, signed by us and by them .

Birth of son, Wlodzimierz Russocki (James) May 29th 1929, Warsaw

Following the marriage she became Countess Irena Russocka, wife of Count Zygmunt Russocki, and together they raised a son, Włodzimierz (later James), in the cosmopolitan world of interwar Warsaw.

A Childhood on the Edge of Catastrophe

James's memories of his childhood are vivid and often humorous, shaped by contradiction - freedom and constraint, tenderness and discipline, wealth and emotional distance. He recalls family outings to Philip’s Café in Warsaw, playing aboard a cabin cruiser on the Wisła, and summers spent at the family estate near Lwów, now lost to postwar Soviet borders. There were governesses, boarding schools, and pranks; he called his prep school “Devil’s Island,” from which he eventually managed to get himself expelled by stabbing the principal's son in the hand with a Boy Scout knife.

Countess Irena with a very young Włodzimierz

He describes hiding from his governess in the many rooms of the estate, observing the rituals of his grandfather Pawel Rothenberg - who gave him hand-built wooden toys from the lumber mill and secretly downed a shot of vodka before breakfast each day. That same grandfather had once been a visible Jewish landowner in eastern Poland. But by the late 1930s, such visibility came at an increasing cost.

“My father,” James remembered, “taught me that the Jews were Polish citizens first, that they deserved equal rights, and that they were deeply committed to their religion and traditions. I always remembered those lessons.” But these liberal values were increasingly at odds with rising antisemitism in Polish society and government. Irena herself, born Jewish, was now living as a Catholic countess. Her dual identity - once a private matter - would soon become life-threatening

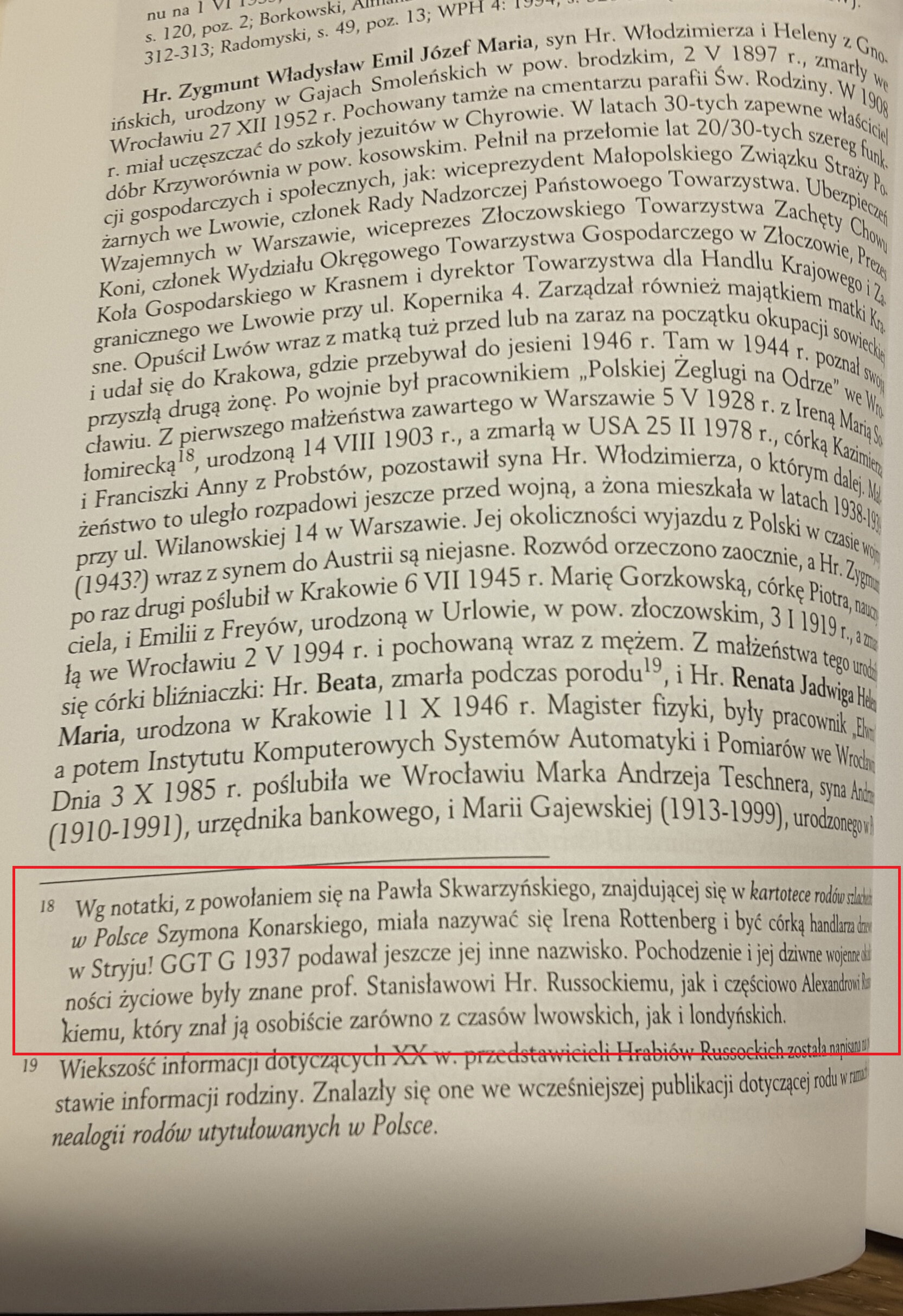

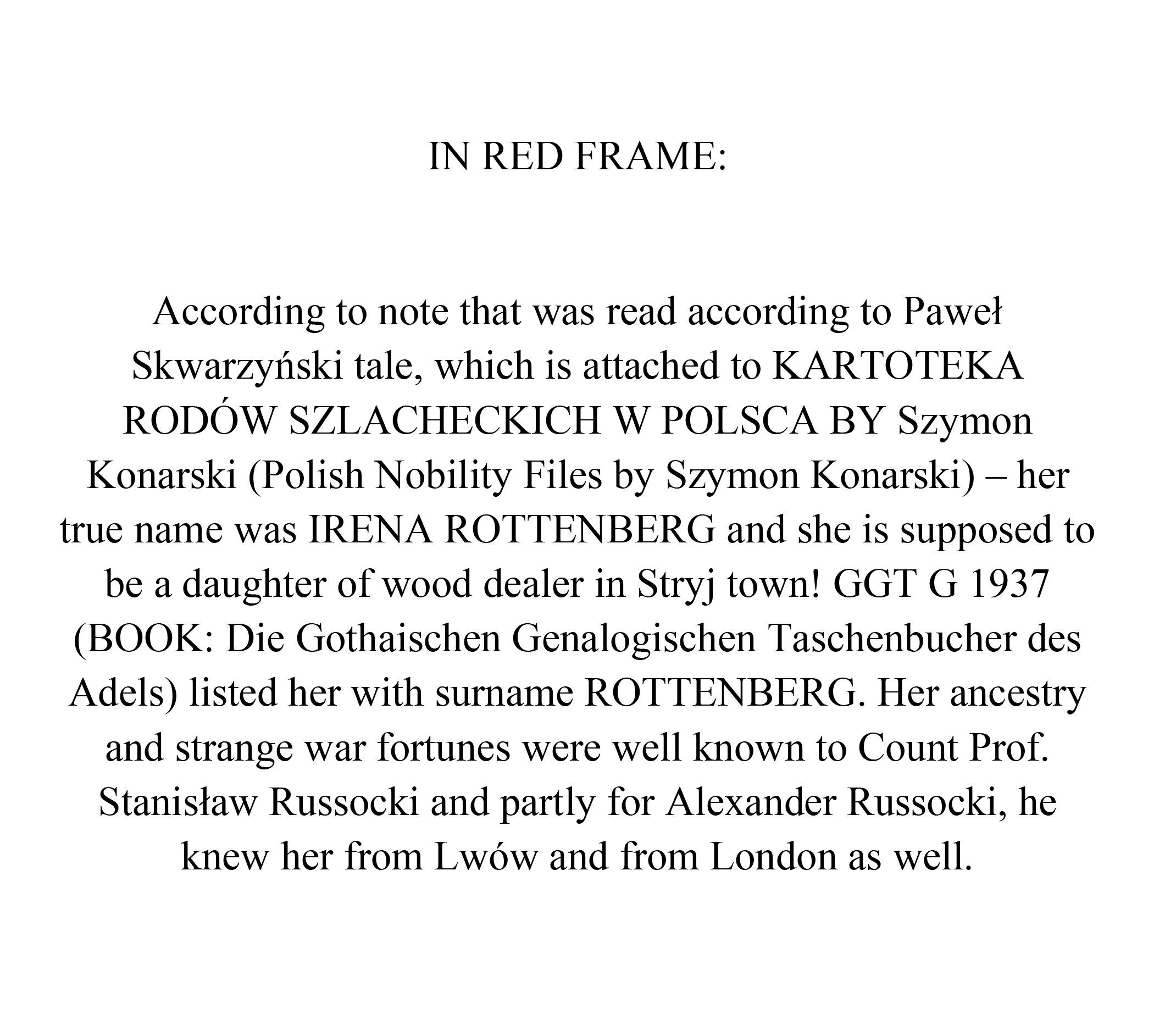

The mystery of Irena’s true identity.

The Russocki family’s genealogy has been studied by experts such as Tomasz Lenczewski, who noted that Irena’s Russocki relatives were reticent to publicly discuss her lineage, a reflection of the era’s social pressures and the stigma attached to Jewish ancestry. Notably, Irena herself did not disclose this origin to her son James (Włodzimierz) Russocki, who never knew of it. Contacts within the broader Russocki networks, including noble lines in London, corroborated the sensitivity surrounding these family histories.

Alexander Russocki from London, who knew Irena, Countess Russocki, asked me to write the monograph of the whole Russocki clan. I had known Prof. Stanislaw Count Russocki in Warsaw very well. His family were nephews of Zygmund Count Russocki, the husband of Irena. Alexander, and also Stanislaw and his sister Jadwiga, told me about Irena. Countess Renata Russocki, Zigmund’s daughter from his second marriage, lives in Wroclaw, but she does not know much about Irene (probably her father didn't like to tell her about his first wife). But Renata was in contact with her brother Wladimir. Wladimir (James) was in contact with Alexander Russocki from London (another noble line of the Russocki family, calvinist; the Count line was catholic)

It is so interesting that Irene didn't talk to James about her Jewish origin. You suggest that he never heard about this origin until the last day of his life? I found the information about it many years ago in the private archive of Simon Konarski - the great Polish genealogist from Paris. I do not have the original note or the date, but it was probably 50-60 years of the 20th century. Naturally, the families in Poland know about her origin. Probably other people also (who know her as the daughter of a timber merchant in Stryj).

I think that Irena (maybe her father?) changed the name from Rottenberg to Solomirecka officially after the First World War. It is possible to find it, but it is strenuous. We should look for several periodic "Monitor Polski" - 1918-1928. These official changes were published in the special periodic (all changes of names)

I tried to publish the genealogy of the Russocki family in Germany in the official periodical of nobles, but the family (Wladislaw Russocki, the son of Professor Stanislaw, and the daughters of James) were not interested in this matter. So, it was published earlier in my book, The Titled Family in Poland, Part 1

I put Irene's date of birth as 1903 (probably in the Gothaische Genealogisches Taschenbuch fuer Grafliche Hauser 1939, her date was 1908!).

Women lying about their age is very common in genealogical research, and not only women. I once wrote a journal article about a Polish political émigré who lived in the UK, claiming he had been born in 1920. He said he was 19 in 1939 and had taken part in the war. But I later found his birth certificate (metryka) in Belarus: he was actually born in 1925... But that’s another story.

As for Irena, I believe she was accepted, especially in Warsaw society. I’m not sure what Zygmunt’s parents thought about the marriage. However, there were some scandals in the Russocki family regarding marriages from the 19th into the 20th century. There are records of Polish counts marrying Jewish women, not only for money, but also for love.

Naturally, I don’t know when Irena met Zygmunt. He is believed to have had an estate near Kołomyja, possibly with a forest, perhaps even timber operations. Could he have had any business connections with Pinkas Rottenberg?

Irena, her husband Zygmunt Russocki, and sister Helena

War and Flight 1939–1940

In the final days of August 1939, as tensions mounted across Europe, the city of Warsaw braced itself for war. Irena and her ten-year-old son, James, lived in a well-appointed apartment near Łazienki Park. Her husband, Count Zygmunt Russocki, was called up to serve with his army unit, leaving Irena with James amid the encroaching threat of invasion. Like many in Warsaw, they participated in building makeshift trench shelters in the public parks - a civic effort encouraged by the state and driven by both fear and patriotic fervour. The press, still under the control of the Sanacja regime, offered a dangerously optimistic view of Poland's military preparedness, claiming that German tanks were constructed of plywood and that any invasion would be swiftly repelled.

That illusion was shattered on 1 September 1939, when German aircraft began bombing Warsaw. The Luftwaffe’s relentless assault ushered in the first horrifying days of what would become six years of war and occupation. For James, the war began with what felt like adventure - the rush to flee the city in their black Citroën, heading east with friends away from the advancing German army, toward the hope of safety. The excitement disappeared, however, when a bullet narrowly missed James while he and his mother searched for food in a small town on the route. It was the first moment he felt the true danger they faced.

Irena in Warsaw. Date unknown.

Irena’s initial refuge was Lwów (now Lviv, Ukraine), where the family had an estate. For a time, they found relative comfort in the best hotel, awaiting what many believed would be a Polish military resurgence. Unbeknownst to most civilians, however, Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin had already signed the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact in August 1939, a secret agreement that divided Poland between Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union. On 17 September, Soviet troops invaded from the east. With terrifying speed, Eastern Poland—including Lwów—was absorbed into Soviet territory.

The NKVD (Soviet secret police) began systematic arrests of Polish intelligentsia, landowners, and officers. Irena, fluent in Russian, Ukrainian, French, German, and Italian, quickly assessed the danger. She understood that their noble background and education made them likely targets for Siberian deportation. Choosing what she saw as the lesser of two evils, Irena made the extraordinary decision to flee back into Nazi-occupied Poland.

By this point, the Soviets had confiscated the family’s car. The return journey to Warsaw was clandestine and arduous, requiring covert passage across both Soviet and German front lines. Irena hired a guide - paid in gold rather than worthless currency - who led them, along with other escapees, in wagons hidden under straw. They slept in peasant huts, where they endured lice, bedbugs, and the cold. James, plagued by a childhood allergy to eggs, suffered hives aggravated by insect bites, yet he pressed on, forced to grow up rapidly under the pressure of survival.

Near the German-Soviet boundary, they waited until nightfall to slip through the forest. It was midwinter. Snow covered the ground, and the cold was severe. As they moved silently through the woods, hiding from Russian patrols, James hands and feet went numb. At dawn, they encountered Wehrmacht soldiers, and Irena courageously called out and addressed them fluently in their language. Mistaking her for a fellow German, they offered warmth and chocolate liqueur to her and her son, then helped arrange their onward journey by train to Warsaw.

Upon returning to their apartment, which remained miraculously intact, Irena attempted to resume a semblance of normal life. She financed their household by selling jewellery - gold and diamonds retained from her pre-war life. But quickly, the brutalities of the Nazi occupation became apparent. To secure food rations, they were required to register with the German authorities. An SS officer, upon discovering Irena’s apparent German ancestry, encouraged her to apply for Volksdeutsche status - a reclassification that would grant them German citizenship and associated privileges, including access to better rations, unregulated fuel and electricity, and exemption from persecution. Irena refused. On their way out, the SS officer kicked James. “They planted the seed of hatred of the Germans in me on the way out of that office. The SS officer kicked me in the ass as we were leaving his office.”

Irena’s sister Helena (Malie Rothenberg, later Helena Lis) and her husband Stanislaw Lis were, by then, believed to be in England, evacuated alongside the Polish government-in-exile. Irena managed to place a Swiss consular notice on their apartment door, marking it as under the protection of the Swiss Embassy - likely a strategic effort to ward off looting or arrest. Although German soldiers searched the building more than once, the Russocka apartment remained untouched for a time.

Their residence, large and well-appointed, included servants’ quarters and a governess, more companion than tutor for James. Amid these relative domestic comforts, life continued under siege. In school, James rebelled against the severity of the Catholic education system. After assaulting a nun and then a Jesuit priest in two separate incidents, he was eventually sent to a more lenient public school, where he finally settled.

In these early war years, Irena carefully balanced survival, identity, and defiance. Her refusal to accept Volksdeutsche status, her strategic navigation of both Soviet and Nazi occupations, and her determination to maintain dignity despite persecution testify to her intelligence and moral clarity. While outwardly maintaining the appearance of compliance, she resisted in subtle, determined ways, ensuring both her survival and that of her son through one of the darkest periods in European history

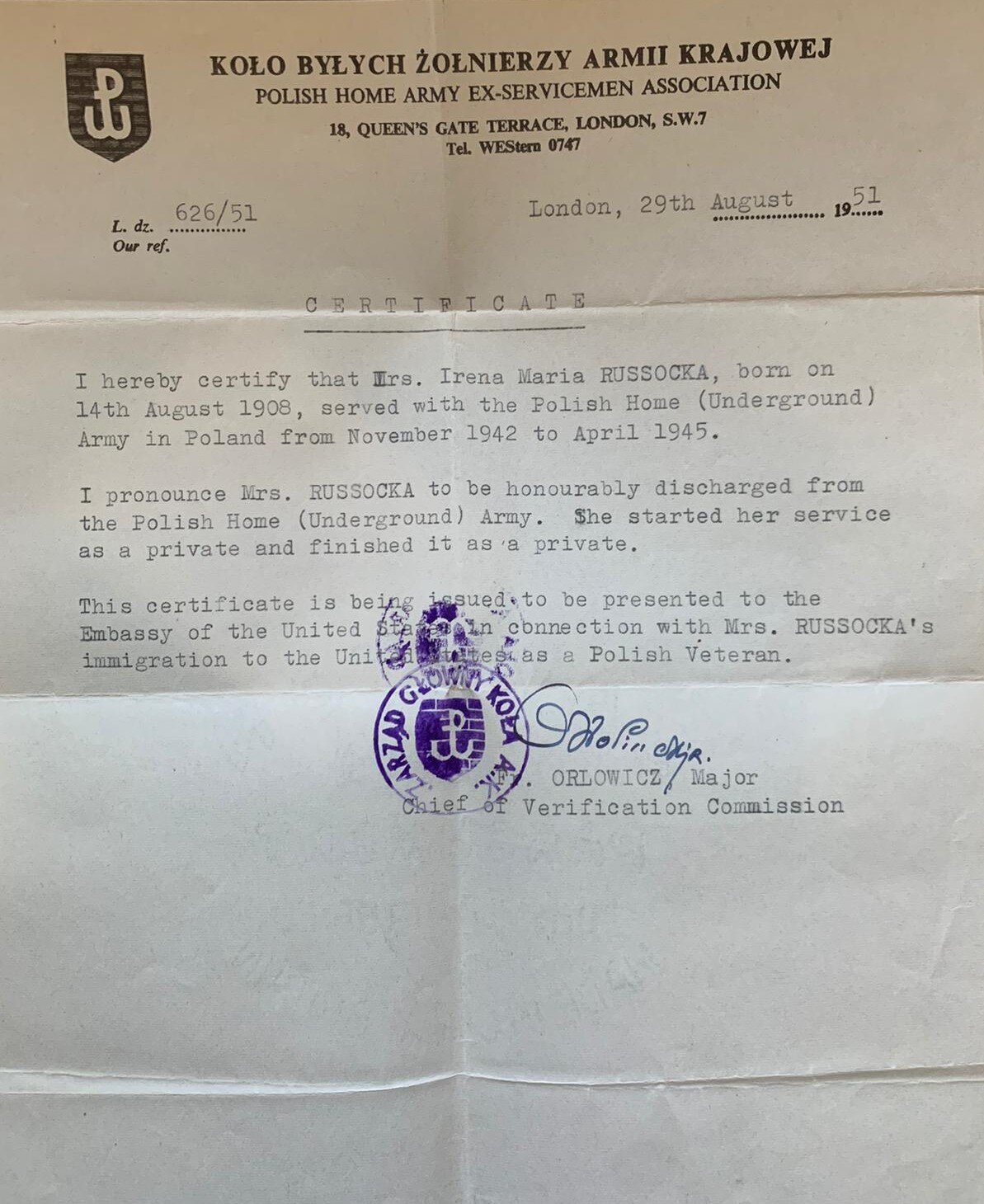

During the Second World War, Irena was active in the Polish resistance. Documents show she was enlisted in the Armia Krajowa (AK)—the Home Army in November 1942, a date which opens two possibilities: either she joined the resistance late or was absorbed into the AK from another underground organization such as the ZWZ. Notably, her enlistment date aligns with the formation of Żegota, the Council to Aid Jews, which operated under the AK. Żegota included a Children's Section whose members worked to rescue Jewish children by placing them with Polish Catholic families and providing forged documentation. Given her background, social standing, and language skills, Irena would have been an ideal candidate to participate in this clandestine work.

Hiding Moshe, August 1942

The apartment building where Irena and James were living in 1942/3

In August 1942, Irena (who was working with the Polish Resistance) took in a starving Jewish boy aged about six or seven whom James found on the sleeping on their street. His name was Moshe and he escaped from the Warsaw Ghetto. She hid and cared for him for 7 months, hoping to get him to safety. This was impossible, with the Germans patrolling the entrance and exits to the city.

“In the late summer or early autumn of 1942, a small child appeared on our street. I noticed that he slept in doorways. He was about six or seven years old - skin and bones - dressed in rags that clearly hadn’t been washed in months. The poor boy turned out to have escaped from the Jewish ghetto in Warsaw and had been hiding. I took him home, and my mother immediately put him in the bathtub and had his clothing burned. There was no question in anyone’s mind that this child needed to be helped.

My mother’s first thought was to find a way to get him out of Warsaw and hide him in the countryside, possibly with the partisans. The problem was how to get him past the German checkpoints. The entrances and exits to the city were all patrolled, and identity documents were thoroughly checked. So, we decided he would stay with us until we could find a way to get him out. We created a hiding place for him in the pantry, behind a false wall, where he could retreat in case strangers came to the front door. He was rarely allowed outside - we were afraid someone might recognize him as Jewish. That would have been disastrous. If discovered, he would have been lucky to end up in a concentration camp. More likely, he would have been shot on the spot. He stayed with us for about seven months. His name was Moshe, but I called him Moishe when we were alone. When others were around, we called him Piotr - Peter. If I ever knew his surname, I don’t remember it now. In the end, perhaps it was safer that we didn’t know or couldn’t remember.

On March 7, 1943, Moshe went out to buy a pack of cigarettes for my mother, just four or five blocks away. Shortly after he left, the Gestapo - the dreaded German secret police - appeared at our door. Someone had reported that we were hiding a Jew in our home. We were arrested and taken to Gestapo headquarters in Warsaw. That was the last time I saw my mother until after the war.

We never found out what happened to Moshe…… I wish I knew whether he survived.” - James Russocki

On March 7th 1943, Irena and James were arrested and taken to the Gestapo Headquarters in Warsaw. They were seperated and James was sent to Mauthausen Concentration Camp. They were not to see each other again until they met in Vienna after the war. James was 13 years old. It is not known what happened to Moshe.

Resistance to Refugee

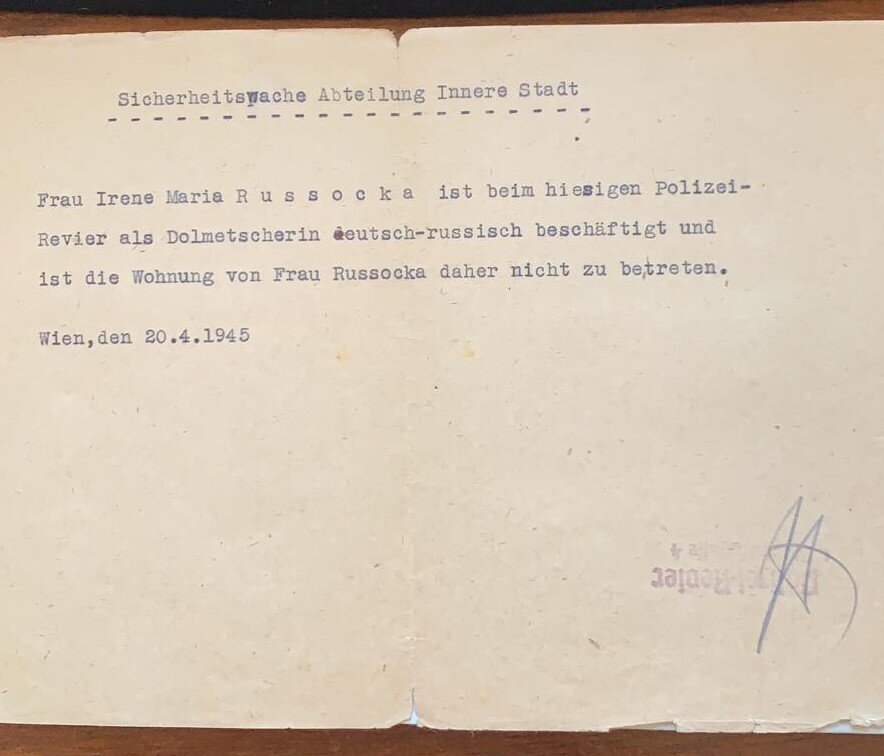

Irena was affiliated with the Armia Krajowa (AK), the Polish resistance. Her social standing, command of languages, and assumed noble identity made her well-positioned to participate in underground networks. Shortly after she and James were arrested by the Gestapo, Irena was released and reappeared in Vienna, possibly under a false identity or as part of a prearranged underground operation. James was sent to a concentration camp.

Confirmed Incarceration and Escape

According to Irena's postwar statement, she was:

Arrested by the Gestapo in Vienna in January 1945 and imprisoned at Rossauerlände internment camp.

From February 7, 1945, to April 1, 1945, held at the SS concentration camp in Oberlanzendorf (near Schwechat, Vienna).

When the camp was evacuated to Dachau at the end of March 1945, she escaped during the transfer.

Earlier Red Cross documents suggest that from December 1943, she had already been imprisoned at Rossauerlände, possibly under suspicion for underground activity or falsified identity. This would mean she was in Gestapo custody or SS-run facilities continuously for over a year and a half, from December 1943 through April 1945.

The location of Oberlanzendorf, a little-known subcamp, and the proximity to Schwechat Airport (a major Luftwaffe and SS logistics hub), suggest that she may have been involved in forced labor or detained under particularly brutal conditions. Escape during a transfer to Dachau, a major concentration camp notorious for its death marches in 1945, was rare, and almost certainly perilous.

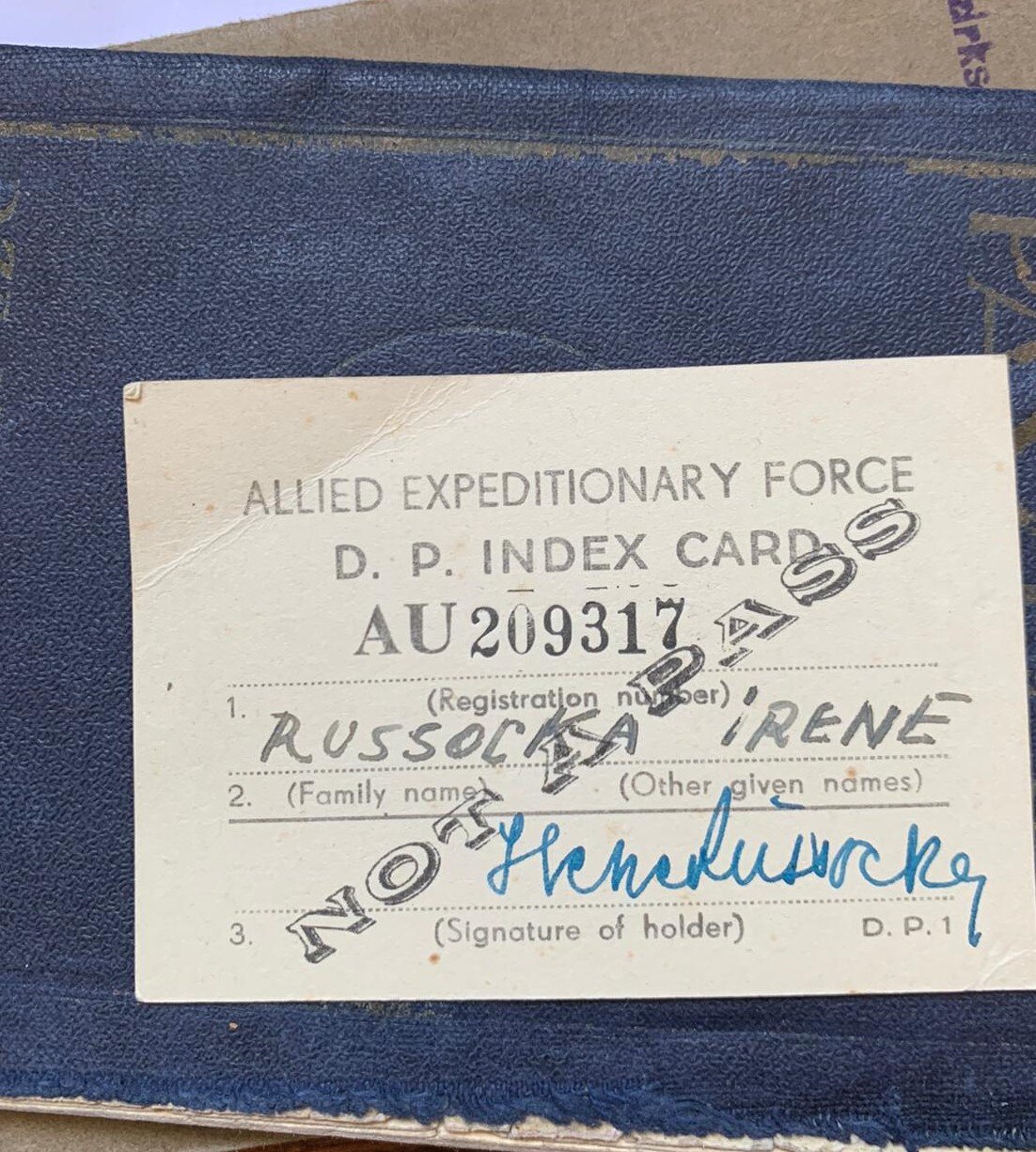

Despite these experiences, Irena managed to remain in Vienna after the war, where she appears again in Red Cross records as a "stateless" displaced person with the title "officer with statutory authority." Her ability to remain in the Soviet-occupied sector until late 1946 or beyond may suggest continued involvement in relief or underground work, or simply her reliance on forged or ambiguous documentation.

On December 27, 1951, Irena emigrated to the United States, likely sponsored as a displaced person under U.S. immigration programs. She is listed as stateless on arrival - another marker of the loss and complexity of identity caused by war.

Archival Summary Based on Tracing and Documentation File No. 880.470 (Wiener Library, 2024)

This summary is drawn from a 30-page Tracing and Documentation (TD) file held by the Wiener Library for the Study of the Holocaust and Genocide. The file, originally assembled by the International Tracing Service (ITS), details efforts to establish Irena Russocka’s wartime persecution and her eligibility for postwar compensation under German restitution laws.

Her escape during the camp evacuation in April 1945 suggests extraordinary courage and likely saved her from deportation to Dachau, a camp notorious for its death marches and overcrowding in the war’s final weeks.

Timeline of Wartime Persecution (Based on Multiple Sources in the File)

December 1943, Arrested by the Gestapo in Vienna, imprisoned in Rossauerlände prison (Enquiry Summary Cards, 1963 letter)

7 February 1944 Transferred to SS concentration camp Oberlanzendorf / Schwechat II, Lower Austria

1 April 1945 Escaped during forced evacuation to Dachau concentration campContradiction (Letter, 1968) States arrest occurred in January 1945 and that she was imprisoned in Rossauerlände from that time - possibly an error or sign of confusion/memory trauma

March 1945, Forced on a march toward Dachau but managed to escape en route.

Post-1945, lived as a displaced person in Austria

27 December 1951, emigrated to the United States under an English travel permit with her son James

1963–1968 Filed multiple statements and applications for reparations and witness corroboration, including via her legal representative Ludwig Seidenman

Documentation Highlights

Pages 3–6 (Enquiry Summary Cards):

Outline biographical data, a summary of her path of persecution, and a note on her immigration. These reflect third-party or self-reported beliefs about what happened to Irena and are not direct testimony.Pages 7–8 (Letter, 1968):

Submitted as part of a compensation claim, this letter states Irena was arrested in January 1945, contradicting earlier documentation. It confirms her imprisonment at Rossauerlände, transfer to Oberlanzendorf, and escape during a forced march to Dachau.Pages 9–10:

Identifies Inez von Martiny as a potential witness who could corroborate Irena's experiences in Oberlanzendorf.Pages 11–12 (Letter, 1963):

Affirms that Irena was arrested in 1943, imprisoned in Rossauerlände until 7 February 1944, then sent to Oberlanzendorf until April 1945. States she could no longer recall her prisoner number — a not uncommon occurrence among trauma survivors.Pages 13–18 (Compensation Applications):

Include Irena’s handwritten signature and brief notes on the nature of her persecution. These documents form the legal foundation for recognition of her suffering.Pages 19–30:

contains administrative correspondence about the search for supporting documentation and witnesses, rather than new biographical material.Conflicting Dates and Memory

The conflicting arrest dates — December 1943 vs. January 1945 suggest either a clerical error or the fading/confusion of memory. What is clear is that Irena was imprisoned in Vienna, later deported to a concentration camp, and survived a forced evacuation.

Her escape prior to Dachau’s arrival remains one of the few concrete personal memories she retained, though she did not recall her prisoner number. The absence of such details, along with the multiple names she used, suggests a life deeply shaped by trauma, fear, and survival mechanisms.

Despite filing legal claims and emigration papers, Irena never spoke openly about her experiences to family members. The archival record stands as the only surviving witness to this period of her life

After the War

After the war, a German-issued pass dated 30 April 1945 confirms her presence in Vienna. The city was still under Soviet control, and given the known violence during the Red Army’s occupation, including widespread sexual violence against women, it is striking that Irena was able to secure documentation and protection. This may have been due to her influence, connections, or strategic positioning.

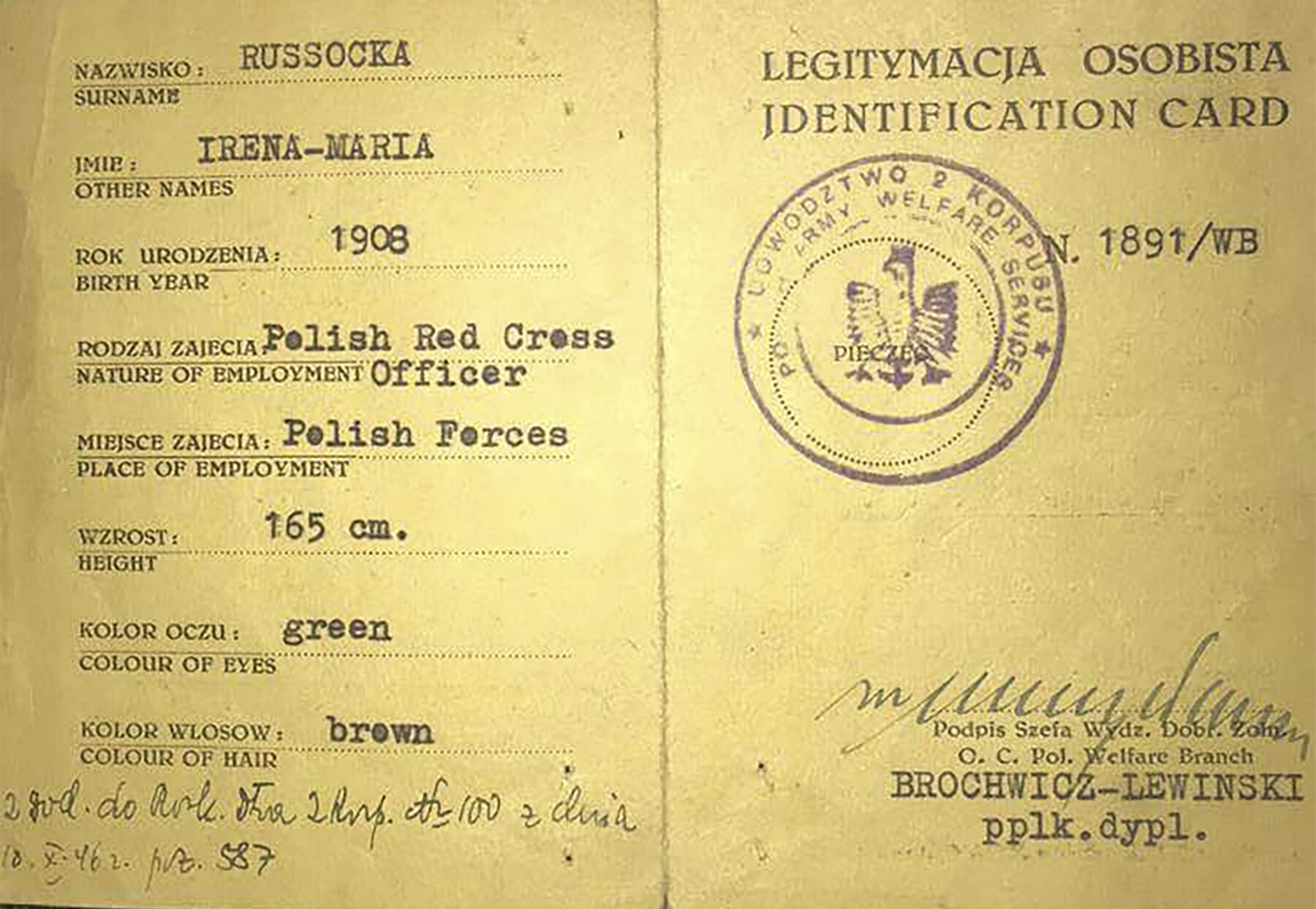

A Red Cross identification card from this period describes her as an “Officer with statutory authority,” implying a role of leadership and trust. This authority was not common and may reflect prior government service, wartime contributions to humanitarian work, or simply recognition of her experience and status. She is believed to have remained in Vienna until at least late 1946 or early 1947, working either with the Red Cross or with displaced persons (DPs), though definitive records are yet to emerge.

In 1951, Irena emigrated to the United States with her son James, by then a survivor of Mauthausen. Declared stateless, she never returned to Europe. She passed away in 1978 in New York. Throughout her life, she consistently deducted years from her age, and at the time of her death, her family believed she was 70—she was, in fact, closer to 78.

Despite a close bond, Irena and James never spoke of their wartime experiences. This silence is typical of many survivors, for whom trauma was endured but seldom shared. Even James, a camp survivor, was unaware of his mother’s Jewish origins—a secret that very likely saved both their lives.